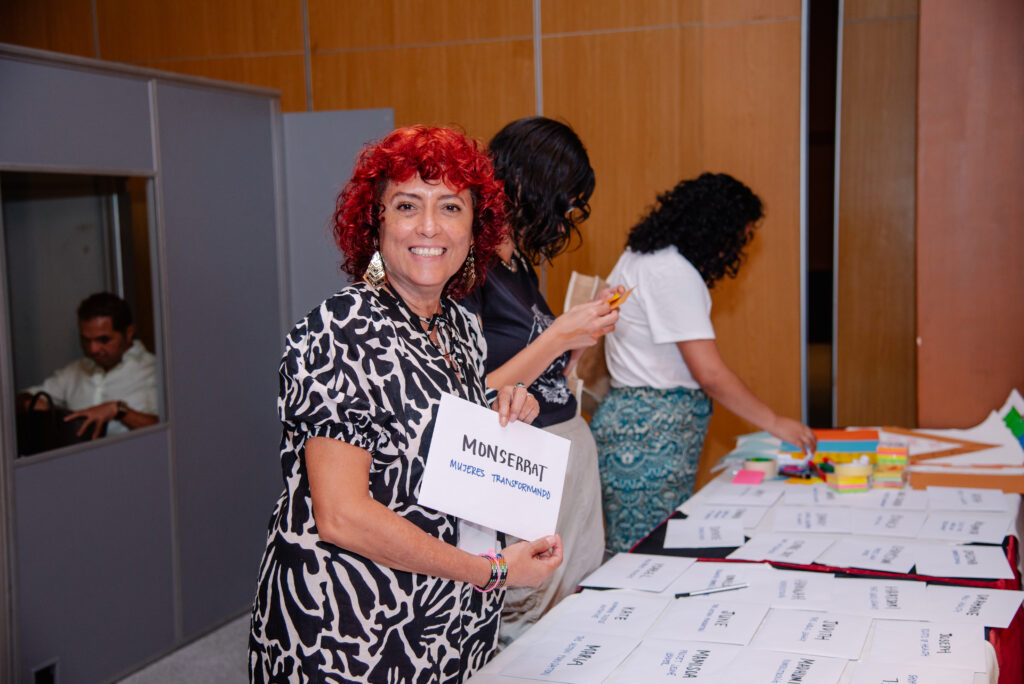

Strong Women, Strong Voices: Interview with Montserrat Arévalo

Montserrat Arévalo serves as the Executive Director of Mujeres Transformando (Women Transforming), an organization dedicated to safeguarding the rights of women, with a specific focus on women employed in maquilas, which are foreign-owned factories or sweatshops commonly found in Latin American and Spanish-speaking regions. Mujeres Transformando actively contributes to dismantling patriarchal systems and power dynamics that infringe upon the wellbeing and autonomy of Salvadoran women. Their approach combines class consciousness and a gender perspective to challenge these oppressive structures.

The organization is committed to empowering women, enabling them to exercise their full and unrestricted citizenship rights. Their projects are strategically designed to:

- Enhance the leadership of women within labor unions

- Conduct investigations into the working conditions experienced by women in maquilas

- Raise national and international awareness regarding the abuses faced by women maquila workers

- Advocate for reforms to laws governing free trade zones

- Develop and publish a Manual of Labor Rights.

This commitment to gender equality and advocacy for the rights of women underscores Mujeres Transformando’s role in advancing social justice and gender equity.

Our Interview with Montserrat Arévalo

Interpretation support provided by WomenStrong’s Hannah Barrueta Sacksteder.

WomenStrong: Thank you for joining us today, Montserrat, and for Mujeres Transformando’s partnership with WomenStrong. Your organization works on some very challenging issues. July 5 marked the 21st anniversary of a chlorine spill in a factory in Santo Tomás, a municipality in San Salvador. The spill affected hundreds of workers. In 2012, in honor of those workers, Mujeres Transformando and other organizations called for a National Maquila Workers Day, to recognize the contribution that workers like those in the factory have made to the national economy and to promote a culture of respect for their rights and protections. Montserrat, has there been progress towards setting a national day?

Montserrat: Well, we were able to create a mobilization effort with the organization, with Mujeres Transformando and the workers at the factories — many of whom are victims of mass chemical intoxication. We successfully garnered substantial support for our proposal, from human rights organizations, the general population, and women representatives of the Salvadoran government.

We successfully presented this proposal to recognize the Fifth of July as the National Maquila Workers Day. On this day, we organize numerous activities to commemorate and raise awareness about labor rights in El Salvador, trying to create a culture of respect for workers’ rights. We advocate for all women, but for the rights of women working in the textile factories in our country. The reason for this is that these are the spaces where violations against workers’ rights continue to exist.

While these violations may not be as dire as they once were, we continue to witness violations of workers’ rights in the textile factories. This includes long and excessive working hours, physically and mentally demanding labor, and very low incomes. Therefore, the National Maquila Workers Day serves not only as a platform to promote a culture of respect for labor rights, but also as a way to recognize and empower the more than 500 workers who were chemically intoxicated, and who were told, “You are fine. You are experiencing a moment of collective hysteria.” Later, it was proven that the chemical intoxication was due to the industry’s lack of health and safety regulations and that a chlorine leak had intoxicated all these people.

WomenStrong: Thank you. We certainly appreciate your efforts to bring awareness and recognition to that day, and to raise visibility for such an important issue. With incidents like what happened in Santo Tomás, do you think the issue lies more with individuals who are not held accountable for their actions, or does what happened in Santo Tomás shed light on a deeper institutional and systemic problem?

Montserrat: I think that we have a little bit of both. At a fundamental level, we exist in a nation with a historical record of not guaranteeing the rights of its people. It is a very weak state, which allows for factory owners, powerful individuals, and foreign entrepreneurs to come into our country with no intention of respecting human rights and no interest in adhering to labor regulations. They establish factories and exploit the local people for their own gain. It is no coincidence that it is in the production section of factories where we consistently encounter rights violations and low incomes.

This situation is not surprising in El Salvador, as the government often turns a blind eye to these practices and allows them to persist. These companies are not going to go to the Global North, they are not going to go to places in Europe and North America, because labor costs — including salaries — are significantly higher, and workers’ rights are actually respected in those regions. Instead, they come to the Global South, where historically, governments do not guarantee our rights.

When we have a government that fails to ensure or protect workers’ rights, it creates an ideal environment for individuals who lack ethical regard for labor rights to thrive. They do whatever they want. They do not see the importance of industrial hygiene, they disregard standard working hours, and they hire anyone, regardless of their qualifications or age — including young girls. That is precisely why I emphasize that at a fundamental level, it is the government that permits these situations. The government allows for an environment where worker exploitation thrives, because workers’ rights are not adequately safeguarded.

WomenStrong: What do you believe is the best way to disrupt, counter, and create meaningful and sustainable change for maquila workers and, more broadly, in El Salvador?

Montserrat: I believe that organizations like ours, which work with factory workers, must consistently offer support to all individuals with whom we collaborate. Our primary goal is to promote skill development and ensure the continuity of factory jobs without disrupting the income sources of these individuals. In El Salvador, where formal job opportunities are limited, many workers, especially women with limited education, rely on factory employment as their livelihood. We do not want the factories to close and leave. What we want is to ensure the continuity of factory jobs while upholding the country’s standard labor rights, with a strong emphasis on respecting these rights in full.

What we want is to ensure the continuity of factory jobs while upholding the country’s standard labor rights, with a strong emphasis on respecting these rights in full.

We know that [the brands] can pay a better wage. It is not just about engaging with the owners of textile factories; we also need to collaborate with major transnational brands. These large corporations have the capability to provide better wages and enhance production processes — reducing the need for constant production rushes. Engaging with these large corporations allows us to establish a working environment where workers can perform their duties under more humane conditions. Setting such tight deadlines without providing adequate incomes only leads to increased stress among the workers. This does not help them escape poverty; instead, it puts them at risk of injuries and illnesses, including chronic conditions, as mentioned earlier. To me, it is of utmost importance to continue monitoring and evaluating the state’s role in safeguarding labor rights, as well as ensuring the effective implementation and enforcement of these measures.

Then we want to see what we can do in the Global North, specifically in the consumer sphere. We want to see how we can strengthen our movement to encourage ethical consumer behavior. It is important for consumers to consider the story behind the clothes they wear and the brands they choose to support. Understanding the experiences of women in the Global South and the conditions they face is vital. We need to raise awareness of the importance of fostering a culture of mindful consumption — do not just consume to consume. It is quite concerning to witness the rapid pace at which fashion shifts every 15 days, with each new season prompting excessive consumption. We do not need this. Ethical consumption entails understanding the significance of quality in each garment. Quality means that the clothing item was made while safeguarding the rights and wellbeing of the workers. We should actively promote what it is that we do on multiple levels, at a national level and within our organization. It is essential to ensure that workers are well-informed about their rights [and to] strengthen their resolve and empower them, while working with the government to create and enforce laws.

Addressing the impact of large transnational brands requires the support of consumers and international movements that stand in solidarity with these efforts. In many instances, we have learned that it is faster to resolve conflicts when we have the support of consumers and international solidarity, rather than going through the legal route. Like I said, justice in this country is not quick; it doesn’t follow through, it is delayed, and it favors the entrepreneurs. So, we have sometimes had success resolving issues through mobilizing the international community, through putting pressure on brands, and we have been able to do this with the support of many responsible consumers.

WomenStrong: Mujeres Transformando works on empowering women to realize their full potential, addressing power dynamics, patriarchal deconstruction, and bringing an end to abuse in factories. With this work, where do you see the most impact? How are you able to create change?

Montserrat: What has allowed us to see an impact in our work is a strategy of personal empowerment. This strategy serves as the foundation for all other initiatives we promote, ensuring the sustainability of our efforts and other endeavors. So, what does this personal empowerment strategy entail? It involves a process of self-construction, autonomy, and self-esteem strengthening. It aims to raise awareness among individuals that they have rights, and it encourages them to recognize and reject workplace violence, exploitation, and mistreatment. It is for them to realize that this treatment is not normal, and that reporting a violation of your rights does not mean you are betraying your employer. Employment is an exchange. Yet, so often in that exchange, the worker gives much more than they receive. As they become increasingly aware of these issues, they gain the ability to file complaints, engage in grassroots mobilizations, speak to the labor minister, provide testimonies about their experiences, and establish connections with fellow workers. As a result, we can see the lasting effects of our advocacy efforts.

While in some instances, Mujeres Transformando serve as the public representative, due to workers’ inability to do so over fear of dismissal, the ideas and proposals originate from the workers themselves — stemming from their specific needs. And when they can, they accompany us. They are there; they participate. That’s how we achieved not only the declaration of the National Day of Maquila Workers in El Salvador, but also persuaded the government of El Salvador to subscribe to ILO Convention 177 on home-based work. Through the empowerment process, we have achieved significant impacts. Without empowering the workers, even if we had taught them about labor codes and international conventions, they would not have felt the strength or the right to demand compliance. Therefore, our initial focus on empowerment has paved the way for other significant changes.

For example, some of them have taken their own legal action, and we have seen home-based embroiderers win their lawsuits, not just once, but two or three times. This has resulted in the establishment of legal precedents in the country for any home-based worker seeking to enforce her rights. Before, there was no legal precedent that could demonstrate, “home-based workers can file lawsuits, and there are cases we can cite where they have prevailed.” Therefore, these significant impacts are essential.

However, for those of us who firmly believe that the personal is political, other equally valuable impacts include a woman realizing that working overtime will not lift her out of poverty and will only negatively affect her health. Here, they are paid in cents, so a woman may decide it is more worthwhile to attend a workshop or training rather than working overtime. Alternatively, she might choose not to give a 100-percent effort to protect her body from permanent injury, opting for 80 percent — enough to not be harassed by factory management and to protect her health.

Home-based embroiderers are becoming more aware of the physical toll their work takes, leading them to discourage their children from engaging in such labor. These personal impacts at the everyday level are truly valuable. They include reclaiming the right to organize and to defend their membership in organized groups, even in the face of pressures from their employers and controlling life partners; men here tend to be very jealous and controlling. These women are setting an example for their children. Additionally, women are asserting their rights to socialize with peers, enjoy leisure activities, and even take a day off at the beach. Over the 20 years of our work, we have witnessed the growth and development of women, both those who have been with us for two decades and those who have recently joined our organization.

WomenStrong: How does the status of women workers in El Salvador compare to the status of those in the rest of the world? How do the challenges and successes compare?

Montserrat: I believe that the situation of textile workers in El Salvador is very similar to that in other countries in the region. In terms of dynamics, pressure, and labor rights violations, it closely resembles the conditions in Asia. However, it is worth noting that in Asia, the workers earn even less than the workers here. So their situation is even more precarious, particularly in terms of salary and working conditions. There have been cases of factories collapsing, like the tragic Rana Plaza incident (in Bangladesh, in 2013), resulting in many deaths due to shockingly poor working conditions. Despite these differences in salary and conditions, the similarities persist, including long hours, low wages, and the denial of the right to unionize or join any other type of organization.

But I believe that here in El Salvador, we have made great strides since the 1990s, when the textile industry was introduced. Over the years, we have continuously worked on organizational and union initiatives to advance workers’ rights and expose violations. In the past, workers could be subjected to physical abuse by their supervisors, including beatings for failing to meet production targets. It was common for them to endure harsh punishments, such as being forced to stand in the sun for extended periods, resembling medieval-like punishments.

So, as we exposed all of that, raised awareness, and acted, things gradually began to change. For example, pregnant women can no longer be fired, although gender bias still exists in who tends to be hired. But the clinics in the factories focus heavily on family planning. They show little interest in sexual health. One specific aspect is the administration of contraceptives because, of course, they aim to prevent women from becoming pregnant. So these gender biases persist. Naturally, if you are already pregnant, they cannot terminate your employment.

So, there is no more physical and verbal abuse. Pressure and harassment persist, as there are instances of power abuse and negative communication, even without resorting to insults. However, these aspects have evolved. We introduced regulations that were approved at the time, leading to improvements in working conditions. But if you delve deeper, you will find that these are the areas the textile industry resists changing because that is where they amass their wealth. This includes reproductive issues, low wages, and the criminalization of organizing. These areas are considered non-negotiable.

For instance, permission for any situation that requires a worker to leave their workstation has not changed. In the factory, a woman might hesitate to say, “I received a call from the school, and I need to go,” because she knows that even if she is absent for just a few hours, they will deduct a full day’s pay from her. They will also deduct her Sunday benefit, which is her paid day off. These issues continue, although I do believe that we have made progress and achieved significant changes. Nevertheless, exploitative conditions, discrimination, occupational health concerns, and workplace hazards continue to prevail in the textile industry.

In the factory, a woman might hesitate to say, “I received a call from the school, and I need to go,” because she knows that even if she is absent for just a few hours, they will deduct a full day’s pay from her. They will also deduct her Sunday benefit, which is her paid day off.

WomenStrong: Recently, you have focused your efforts on your 13th annual Meso-American Meeting of Textile Workers, Embroiderers, and Weavers and an international symposium called, “We Want to Be Alive and Free.” Can you tell us more about those gatherings, their goals, and outcomes?

Montserrat: We are an organization with an international focus, which means that the problems we tackle have global implications. Globalization affects every corner of the world, causing damage to ecosystems and depleting resources. Our belief is that these issues will ultimately harm us all. Therefore, we consider internationalism a powerful driver of change. In line with this perspective, we have been fostering collaboration and information exchange among organizations addressing similar issues.

Especially in our region, Central America, it is common for factories to relocate from one country to another. They might move from El Salvador to Honduras, then back to El Salvador, or they might shift their operations to Guatemala, then to the Dominican Republic, and so on. Given this situation, we saw the value in bringing women workers together, across borders.

For example, workers in El Salvador expressed concerns about factories threatening to close if there was no production and planning to move operations to Honduras. The workers were worried about losing their jobs. So we started organizing small meetings, bringing together women workers from Honduras and El Salvador, and they realized they were facing the same threats. The factories were employing the threat of closure as a form of coercion and pressure. As workers communicated and became aware of this tactic, their anxiety levels decreased, and they ceased to be manipulated by it. That is how these exchanges started — small ones initially, between five workers from one place to another.

As we grew, we included other organizations, and this led to Mujeres Transformando being the pioneer in proposing a regional agreement of Women for Dignified Work. We are part of it, along with several organizations from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Now we don’t only work with textile workers, but also with paid domestic workers, agribusiness, and Maya workers and weavers, because we observed similarities in the conditions in southern Mexico.

We saw how important it is to connect with these women who are creating alternative models through cooperatives to generate income while preserving their valuable ancestral wisdom. There is an effort to reclaim weaving as a heritage of Indigenous peoples. So we started building connections and have been developing a series of annual meetings. We bring together 30 workers from Chiapas to Honduras. These gatherings usually take place in El Salvador, since Mujeres Transformando organizes them. During these meetings, we engage in various discussions on economic matters, the political and sociopolitical context of our region, and we also address self-care and the importance of investing in it.

This past year, as Mujeres Transformando celebrates its 20th anniversary, we organized an event with a similar focus. The event was titled “20 Years of Being Fighters,” where we reflected on the impacts of neoliberalism on women over these 20 years. The event served to create a timeline of successes and challenges faced by organized women and workers and outlined future projections. It empowered the workers to see themselves as strong and united, recognizing that coming together and coordinating is valuable and necessary. We crafted a final declaration which highlighted the reflections made by the women regarding their individual circumstances and the demands they have for their respective states. These demands encompass a wide range of issues, including the protection of natural resources, addressing metal-mining concerns, dealing with hydropower projects that take water from towns and communities, enhancing legal protections, and advocating for better wages.

The successful meeting celebrated the resilience of the participants as fighters. Furthermore, we organized an international symposium titled “We Want to Be Alive and Free,” to address the violence faced by women and girls. The symposium brought together international and national experts. On the first day, we discussed the topic of vicarious violence, which is violence directed at women through their children. These cases often involve women with shared custody who entrust their children to their ex-husbands for a weekend visit, only to have the children not returned: they disappear. This is a way of punishing women through their children. In some extreme cases, the children have been murdered, as a means of inflicting pain on the women.

The symposium featured experts from both Mexico and El Salvador who discussed this topic, along with testimony from a mother currently facing over 200 legal proceedings as she fights to have her son returned from her ex-husband. This was the focus of the first day of the symposium. It became apparent that, in El Salvador, there are gaps in the law, especially in terms of legislation aimed at ensuring a violence-free life for women, as [current law] does not specifically address this type of crime, which is occurring. Many attendees shared their personal experiences, with one woman stating, “I have been a victim of this type of violence, both as a daughter and as a mother.” It was very striking to realize all of this and to see that there is still much work to be done because, in El Salvador, we need to include it in the law.

During the second day of the symposium, we focused on workplace and economic violence. Mujeres Transformando, along with an organization from Guatemala and colleagues from Chiapas, Mexico, contributed to the discussions by presenting alternatives to exploitative labor practices and mistreatment in factories. These alternatives were centered around economic initiatives based on the principles of cooperativism, offering a way to combat workplace violence and create more equitable economic opportunities.

On another day, we discussed obstetric violence, a critical issue in El Salvador due to the complete criminalization of abortion. In our country, not only is abortion illegal, but women who enter hospitals with suspected abortions are also criminalized. This has resulted in the imprisonment of many women, primarily from impoverished backgrounds, including factory workers, who receive sentences ranging from 30 to 50 years for homicide, when they have had obstetric complications leading to abortions. It is essential to underscore that the nature of work in textile factories is a risk factor for women experiencing spontaneous abortions, and we emphasize the urgent need for the decriminalization of abortion as a fundamental human right.

So, we had a day where we focused on this issue, and we invited a representative from the National Campaign for Safe, Legal, and Free Abortion in Argentina. Argentina’s recent success in legalizing abortion has made it a reference point for the feminist movement in Latin America, particularly due to the widespread Green Wave movement. This topic held significant importance for our discussions during the symposium.

We closed the symposium by discussing an extremely painful form of violence that is impacting us all — the issue of femicides and disappearances. We were joined by experts and a lawyer and former prosecutor specializing in femicide cases from Guadalajara, Mexico. Additionally, representatives from the Missing Persons Search Bloc for missing relatives in El Salvador participated. It was an intense week as we confronted these forms of violence, but it provided us with a platform for reflection.

Throughout the week, we came to realize the gaps in El Salvador’s legal and societal frameworks that hinder progress in addressing these issues. We emphasized the importance of raising awareness and understanding that many missing women are not responsible for their fate — they didn’t provoke it, they didn’t “run off with a boyfriend,” they haven’t been involved in wrongdoing. Often, their partners are the ones behind their disappearance, their murder, and have made efforts to conceal the truth. It became clear how vital it is to continue advancing our efforts, because every woman has the right to a life free from violence, and we aspire to create a better world for our children.

The symposium was a very important, valuable, and intense week, but we ended up very united. To channel our energies differently, we closed with an intimate concert. National and international experts lent their voices, to emphasize the path we must continue walking, to secure the right to a life free from violence for women.

WomenStrong: Clearly, you work a great deal in coalitions and collaborations with a range of organizational partners, such as the Concertación de Mujeres por un Trabajo Digno, Alianza por los Movimientos Feministas, Concertación Feminista Prudencia Ayala, AWID, and the Network of Popular Education Among Women (REPEM). Working in coalitions can take longer than it would to do the work on your own. Why collaborate? What are the advantages? What are the challenges you face in this work?

Montserrat: I firmly believe in the importance of building networks and fostering connections with others because it amplifies our collective strength. The effects created by combining knowledge, diverse experiences, and various capabilities enhance the impact of our work. Therefore, I see collaboration as essential, where we unite around a common purpose, pooling our capacities, resources, experiences, energy, and dreams. We are facing very tough, complex issues that can be disheartening. Coming together allows us to lean on and support one another. Here we have a word, “acuerparnos,” (to embrace each other), which signifies putting our bodies together to move forward.

So it is vital to do it together. Even if it takes more time, it involves the skills of negotiation, reaching agreements, sharing visions, and being flexible, even in moments of disagreement. Flexibility, negotiation, and proposing solutions are all part of the process. However, it is crucial to ensure that the entities or individuals we collaborate with are aligned with us in terms of political and ideological principles. We don’t form alliances with just anyone; we choose allies who we know share our values and goals.

We collaborate with those who share the same vision, principles, and values. This is why we are actively involved in various spaces, both at the national and regional levels, and now we have expanded our presence to international spaces. Mujeres Transformando is represented on global boards, which provides us with valuable learning experiences and the opportunity to further elevate the visibility of our region. Which is important for me, because Central America often goes unnoticed. It is not seen, it is not heard, and it is a tremendously unequal and tough region for women and girls.

El Salvador is unfortunately recognized as one of the most dangerous countries for women, as reported by the United Nations. This region is also environmentally vulnerable, yet rich in resources, attracting transnational hydropower companies and becoming a disputed territory for various interests. Personally, not just as a member of Mujeres Transformando but as Montserrat Alvarado, I consider it crucial to bring attention to this region. We need to highlight the challenges faced by human rights defenders and the girls living here, and we aim to garner support from global spaces to focus on Central America and uplift the voices and rights of Central American women.

WomenStrong: What has been one of your proudest moments at Mujeres Transformando?

Montserrat: There have been so many moments that fill me with pride. Achieving the declaration of July 5 (in commemoration of the Santo Tomas chlorine spill) was a significant milestone where we felt immense pride. Another memorable moment was when we organized a public event, and the national theater was completely filled, with lines of people wrapping around the block and eager to attend our event. We had to schedule another function, because there was no more room.

Celebrating the years spent together with my colleagues is also a source of great pride. Seeing women who have been organizing for 20 years and still going strong address me as a partner, and saying, “Old lady, we’re going to keep going, right?” – That was a moment of immense pride, making me realize that the 20 years of hard work, anxiety, sleepless nights, and prioritizing Mujeres Transformando over family at times, have all been worth it. My son, who has shared me with this institution for 20 years, is now 28; and when I see my empowered colleagues standing in front of a company with microphones, boldly declaring, “You violate rights, and we won’t allow it” — those are the moments that make me the proudest — witnessing the growth of my colleagues.

WomenStrong: What has been one of your greatest challenges?

Montserrat: I believe the most significant challenges we will face are in the current context, as democratic spaces are closing, and opportunities for dialogue are shrinking. One of the initial challenges we encountered was the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced us to adapt our working model. Our work is deeply rooted in communities and involves maintaining a constant presence among workers. Transitioning to virtual platforms meant learning to use tools like Zoom and YouTube for training, which was a significant adjustment for us and our colleagues. That was the first challenge we faced.

However, the current context in my country can be even more complex. As organizations in our role, our function includes monitoring whether the state is functioning effectively, providing tools, and offering contributions based on our experience, to help improve [the state’s] performance. This has become more limited, and there will be increased oversight. It doesn’t necessarily mean we disagree with these controls, but it does require us to invest more resources and time in adapting to them.

Obtaining such resources can be challenging, especially in projects funded by public funds, such as those from the Spanish Cooperation, which may have restrictions on certain types of funding. Therefore, we actively seek alternative funding sources to meet the government’s requirements.

I believe that the most complex challenges will be encountered in the current context. Our hope is to continue our work as we have been doing and gradually break down these barriers, reduce levels of distrust, and reestablish dialogue with the government as we did in the past.

Previously, organizations like Mujeres Transformando and other civil society groups could collaborate with the government, present proposals, work together, and achieve significant outcomes for the population. We aspire to reach that level of cooperation again; but in the meantime, the challenges and obstacles are present in the current context. There will always be external factors like disasters, such as tropical storms, or sudden conflicts and territorial issues, all of which can disrupt our work. However, I believe the greatest challenges lie in the sociopolitical context we are facing, and we hope it does not lead to greater instability; more stability would allow us to continue our work for a better El Salvador.

WomenStrong: What is your hope for the future?

Montserrat: At the institutional level, we have a dream that we want to pursue: becoming a reference, not only at the regional level, where we already have a presence, but also a reference in strategic litigation of cases involving labor rights violations. This is a challenge we are eager to embrace, positioning ourselves as an office with expert litigators in areas such as the Inter-American Commission, the Inter-American Court, and all these spaces of strategic litigation. We aspire to take on cases of labor rights violations of workers from the Central American region. This is a dream and a challenge we are actively working toward achieving.

We hope that these efforts will contribute to the establishment of a culture of respect for the labor rights of women in the region. Our goal is to continue promoting awareness so that women in this country and the Central American region can enter the labor market under better conditions.

This includes a vision of shared responsibility for caregiving, where companies, the state, families, and communities all contribute, rather than placing the burden solely on women. This would allow girls to have access to quality education and choose professions and dignified work. These are long-term dreams and structural changes that may not be fully realized in my lifetime, but my contribution is to leave behind transformations that lead to reduced discrimination, sexism, and [that can] empower women and girls to pursue their aspirations with the support of a more equitable structure.

WomenStrong: Thank you so much for your time today, Montserrat. We appreciate you and the work of Mujeres Transformando. As we wrap up, do you have any advice for young advocates and activists who want to ignite social change and ensure justice for all?

Montserrat: My first piece of advice would be to have faith in yourself and your dreams. Believe in your own abilities, and persevere, even when the path seems dry and demotivating. There will be moments when it feels like you are just a small drip in a vast sea, but trust in the importance of what you are doing and keep moving forward. So, believe in your dreams. Additionally, seek connections with other individuals who share your dreams of bringing about positive transformation. Together, you can support each other with laughter, anecdotes, experiences, tenderness, and wisdom. That is how the journey should be; otherwise, it can be very arduous.

WomenStrong: I may ask you one last question. What is your favorite food?

Montserrat: Oh, my favorite food! I love pupusas, which are our typical dish. I adore anything made from corn. My favorite cuisine happens to be Salvadoran. For instance, we have sopa de gallina india here. That means free-range chicken, a chicken that fed on leaves, seeds, roamed freely, and was not caged or given hormones. We call it gallina india, not in a derogatory sense, but because it has a different flavor. So, that soup is delicious! That is my favorite food!

About Montserrat Arévalo

Montserrat Arévalo is a Salvadoran feminist and human rights activist with three decades of experience. She co-founded and serves as the Executive Director of Mujeres Transformando, an organization focused on labor rights for female textile workers. Over the past two decades, she has played a key role in advocacy, policy formulation, and empowerment of textile workers, forging alliances for textile, weaving, embroidery, and domestic workers in Mesoamerica. Montserrat actively engages in national, regional, and international advocacy for women’s rights in the global south, serving on various boards and advisory groups.

She currently serves on the Board of Directors for the Association for Women’s Rights and Development (AWID) and is a steering committee member of the Alliance for Feminist Movements. She also serves as an adviser to the Spotlight Initiative and the Civil Society Advisory Group of UN Women in El Salvador as well as the Inter-American Commission of Women of the Organization of American States (CIM/OAS) for the project, Feminist Alliances to Strengthen the Gender Equality Agenda. She holds a master’s degree in Equality and Equity for Development from the University of Vic in Barcelona and a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the National University of El Salvador.

About Mujeres Transformando

The organization was founded in 2003 in Santo Tomás, a municipality of San Salvador, with the objective of organizing and training the workers of the textile maquila for political advocacy and the defense of labor and human rights. Starting in 2005, an organizational and training process of self-employed women workers began, with the objective of strengthening and linking both employees and the self-employed for the defense of their human rights. Currently, there are 11 groups of maquila workers in seven municipalities of El Salvador, four groups of self-employed workers, and three groups of embroiderers who work for the maquilas.